Stylistically the film, despite its silent era limitations, is engrossing and impactful. Despite it being created in the early 1920s, one could easily argue there are, in fact, special effects in the film. Some scenes have a blue tint, some a reddish (sometimes almost sepia) tone – presumably to delineate day and night. There were double exposures to show a person’s soul leaving their body. The night-time devil's sabbath scenes with the witches flying through the air were also probably very cutting edge for the time. Some of those scenes of imagined debauchery and demons get very surreal. Richard Louw, Christensen’s art director, clearly worked very hard at trying to render the insane and nightmarish accusations and confessions of the witch trials. And, in my opinion, he succeeds beautifully at the task.

But while the visuals of the film are something noteworthy and interesting, the answer the film gives for its main question is highly unsatisfying to a modern viewer. Even in trying to remind oneself of the limitations of what passed for psychology in 1919-22, the film’s premise that it was female hysteria which caused the witch hunts is wholly intolerable. True, psychology was in its infancy at this point in history, and presumably it is tempting for every ‘modern’ generation to think themselves more learned than those that came before. However, for the film to posit, under the umbrella of science no less, that the mass murder of women during the witch craze is somehow attributable to women being driven mad by a roving uterus is simply not palatable for an audience today.

Claiming hysteria was a cause of the witch trials is rank victim blaming on the order of Barstow’s reference to a study by Eric Midelfort. Midelfort actually asserted that women seemed to provoke misogyny and suggested someone should do a study and try to figure out “why that group attracted to itself the scapegoating mechanism.” (Barstow 3). Christensen seems to be saying very much the same thing; that emotionally unstable women caused the entire situation. Though some credit should probably be afforded to Christensen for what seems to be the assertion that, firstly, the hysteria itself is not the woman’s fault, per se; and secondly, that it was a lack of scientific understanding on the part of medieval and early modern society which also contributed. Christensen is at least including the inference that a level of causality, though perhaps not culpability, be applied to the overall society.

Christensen’s now antiquated views on women and that early twentieth century nonsense which passed for psychology, betray what Barstow called “[a] lack of understanding of patriarchy as a historical category” (Barstow 9). Christensen seems to be allowing for the complicity of the society in his assessment that it was their primitive mindset and lack of scientific knowledge that allowed the witch hunts. However, he seems wholly unaware of the role patriarchy played in medieval and early modern society; probably because it had changed little in his own era. It is, no doubt, harder to appreciate the existence of something, like patriarchy, which both oppresses others and benefits you, while one is standing squarely inside it. So, while he does include the broader culture in his assessment of how women were murdered en masse, he is still blaming it on the women themselves (and their hysteria) because they were, and are still to him, an “other.” Christensen doesn’t seem to see or appreciate the role the ‘otherness’ of women in general played in both the witch craze and in his understanding and portrayal of contemporary women suffering from "hysteria" in his film.

Christensen could have seriously benefited from reading a book like Robert Moore’s The Formation of a Persecuting Society. In his genuine attempt to understand how a persecuting society is forged, Moore notes that “persecution began as a weapon in the competition for political influence, and was turned by the victors into an instrument for consolidating their power over society at large” (Kindle Locations 1801-1802), and that “while the victims have changed persecution itself has proceeded down the centuries, constantly expanding” (Kindle Location 1987). Moore’s point being that whether it was lepers, jews, heretics, or women – someone was going to be persecuted because it suited the purposes of those in power, not because the persecuted had done anything to deserve it.

Moore also does an excellent job of explaining how a marginalized group with seemingly little power and a markedly lower social status is seen as enough of a threat to become persecuted. Moore explains that being afraid of someone lower in the hierarchy than yourself was something “very commonly directed against women” because they were “occupying an inferior position while performing essential functions.” The reason for the fear was based on “the danger” that such people would come to understand their actual worth and put an end to an entire “social structure which is founded on the premise of their impotence.” (Kindle Location 1265).

But without the benefit of being able to view the world outside the framework of patriarchy or being able to read Moore’s book and obtain a broader understanding of societal psychology, Christensen pins the entire era of the witch craze on hysteria and lack of understanding thereof. Admittedly, it isn’t fair to judge a person on the basis of information, knowledge, or understanding unavailable to them. And I am not, in fact, judging Christensen. He was probably a lovely person, and he deserves kudos both for trying to understand the past through a modern and scientific lens, and for being less victim-blaming than many of the men quoted by Barstow. Christensen’s film is hampered by turn of the twentieth century conceptions of psychology, but there is a definite attempt to understand and apply context. Also, the general gist of Christensen’s point of view seems to be sympathy – as if to say, ‘isn’t it sad that all this happened because of ignorance about something we now understand?’ The film is archaic and ridiculous to a current viewer, but it is also a visually enthralling legitimate attempt at understanding and explaining a mindset now considered incomprehensible.

Works Cited

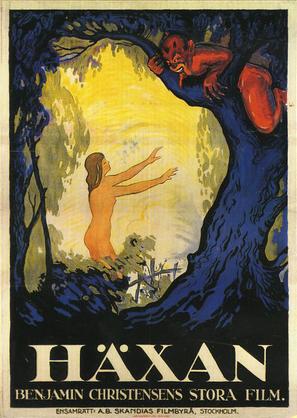

Häxan: Witchcraft

Through the Ages. Dir. Benjamin Christensen. Skandias

Filmbyrå, 1922.

Streaming via HBO.

Barstow, Anne L. Witchcraze

: a new history of the European witch hunts. San Francisco, CA:

Pandora, 1994. Print.

Moore, Robert I. The

Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western

Europe 950-1250. Kindle Edition.

Comments

Post a Comment