A: The concept

of humanness is nothing more than a social construct. And where a living being

falls on the scale of perceived humanness has always been determined by those

with the power to do so (mostly white European men, historically). While the

definition has broadened over time it has not necessarily deepened. True, it

now includes women and non-white ethnicities most of the time, though

obviously animal terms are hurled towards these groups as slurs even to this

day – and to very detrimental effect, including genocide (people were rats in

Nazi Germany and cockroaches in Rwanda). And sometimes, now, it stretches to

include our anthropomorphized companion animals. However, it is still arbitrary

and created and regulated by a handful of the living beings on the planet. And the

disturbing quality at the core of this construct, is the fact that a creature’s

perceived humanness is directly related to what rights will be assigned by the

powerful, and how that being will be treated in both life and death. There used

to be little difference, legally, between a white man’s wife, his slave, and

his horse. An eyebrow might be raised if he killed his wife or raped his horse

but not the other way around, and a slave didn’t even get an eyebrow for

either.

his horse

but not the other way around, and a slave didn’t even get an eyebrow for

either.

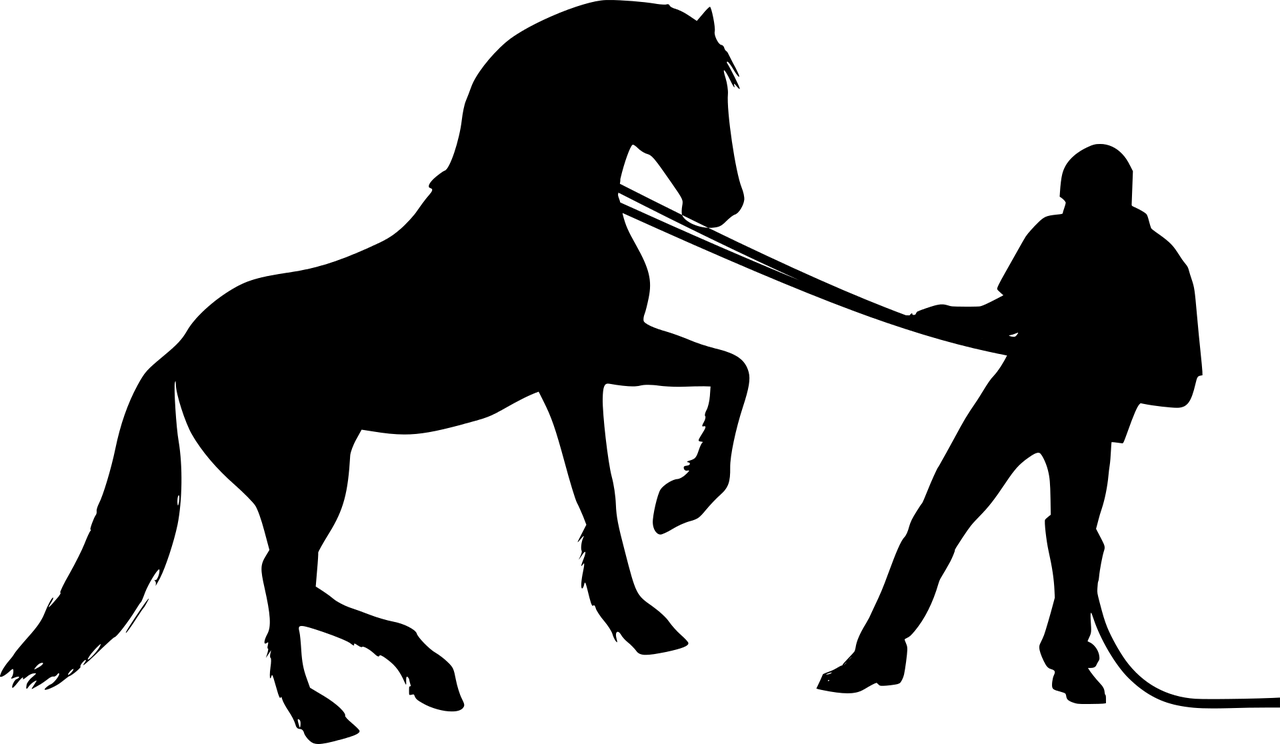

Animals originally occupied a place of fascination bordering on wonder in human thought. They were active parts of our imaginary worlds, in which we assigned them symbolic characteristics and sometimes ever magical powers. Via a combination of familiarity and otherness, we mentally fixated on creatures with whom we had much closer contact than we do now, and yet ones which could not in fact speak to us in a language we understood.

Looking at animals is important because we have largely lost our previous connection to them. Aside from our companion animals, most people are rarely, if ever, exposed to animals anymore. Looking at them, is literally all that a lot of us can do in the modern era, and Berger suggests looking at them is a kind of memorial to that lost past. The fact that animals don’t look back at us the same way, or at least we perceive them to not be returning our gaze similarly, contributes to our sense of distance from them. We go to a zoo to ogle them, and the fact that they largely ignore us while we do so, emboldens us to think they don’t know or care if we spy and eavesdrop. So, we settle into our arms-length distance from them and avoid imagining ourselves in their places.

The videos about Banksy’s art challenge the way we use and see animals in that it reminds us to consider the animal behind the thing. Moving chicken nuggets, swimming fish sticks, cute fluffy bleating stuffed animals poking their heads out of a truck on their way to “slaughter” are all designed to make us stop and realize the sources of the commodities we buy. We are fundamentally removed now, from the truth of where things come from and how they get to us. By and large, there is no more horse or cow out in the barn, usually no chickens scratching in the dirt outside the kitchen door, no more hog wallowing in the mud waiting for kitchen and garden scraps to convert into ham or bacon (and countless other items) that I will participate in converting. Now, we know pictures of chickens, videos maybe, and sleek little bits of boneless skinless-ness that come tightly packed in earth-destroying plastic and Styrofoam, at prices per pound that we grumble about. I wonder how many people eating a BLT could actually point to where on a pig’s body the bacon they’re eating originated.

Comments

Post a Comment